by Nicky Roland

Published British Association of Art Therapist, Newsbriefing, June 2014

The meeting of mindfulness and art therapy is a newly developing area. This gives rise to a potentially rich scope of enquiry into the ways in which art therapists may choose to incorporate mindfulness into their work. What might this look like? Which modalities and therapeutic approaches will inform this process? As Peterson (2014: 55) notes, there is a potential ‘dance’ between mindfulness practices and expressive therapies. In this article, I will explore the ways in which mindfulness practices can be incorporated into art therapy and investigate mindful qualities in art making and mindfulness within the client/therapist relationship in art therapy.

Mindfulness can be defined as:

‘… a state of consciousness, one characterized by attention to present experience with a stance of open curiosity. It is a quality of attention that can be brought to any experience’ (Smalley and Winston, 2010: 6).

Mindfulness is well evidenced in its effectiveness as an eight-week model of practice, based on Jon Kabat-Zinn’s (1990) work. The eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program includes teaching about and practice of mindfulness of breath, body, walking and movement (Kabat-Zin, 1990). There is a meeting of mindfulness and therapy in: Mindfulness- Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). This suggests a value in the integration of mindfulness in existing modalities and provides a reference point as we consider the integration of art therapy and mindfulness.

What needs to be considered in this meeting of modalities?

Many therapists have a predominant modality they draw on in their work, for instance, a significant proportion of art therapists in the UK work psychodynamically. Mindfulness may or may not fit neatly into this model. We have an example of mindfulness being incorporated into an existing modality in Segal, Williams and Teasdale’s (2002) work on developing Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), with its roots in cognitive therapy. When MBCT was being developed, it was not without its challenges. One turning point was the realisation of how vital it was that that an facilitator conveys an ‘embodiment of mindfulness’, and that this could not be derived without the facilitator committing to an on-going mindfulness practice (Segal, Williams, Teasdale, 2002: 56). This is now widely recognised as fundamental to mindfulness facilitation.

When approaching the question of how mindfulness and art therapy can be brought into co-existence it is necessary to examine what is effective, any contra-indicators and the various forms it can take. It is helpful to ask, what are our aims in incorporating mindfulness approaches in art therapy? What do we know of its efficacy? What outcomes do we expect? We know something of the benefits of mindfulness, something of the benefits of art therapy, consideration will therefore need to be paid to the benefits of mindfulness and art therapy together, and whether there may be specific clinical groups or specific problems that may most benefit from this modality.

Thus far, it has primarily been US-based art therapists who have recorded and evidenced their work in mindfulness and art therapy. For example, in Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies (Rappaport, 2014) the intersection of mindfulness and the arts therapies is explored: Peterson (2014) presents her work on Mindfulness- Based Art Therapy for people with cancer ; and Fritsch (2014) presents his use of mindful awareness, body scanning and art therapy with people with chronic pain. Both models are short term and group-based. Other art therapists use mindfulness in longer term and one-to-one work. There are differences in the way art therapy is practiced in the UK and in the US and in light of this, mindful art therapy may take a different trajectory as it evolves here.

Qualities essential to being mindful, such as attentive presence, are inherent in art-making and in a complementary fashion, mindfulness can support creativity.

‘…there are ways in which the arts therapies cultivate mindfulness, present-moment awareness, compassion, and insight, and ways that mindfulness fosters awareness of and attunement with the creative pulse of life itself’ (Rappaport, 2014: 4).

In examining the meeting of art and mindfulness, Rappaport notes that artistic practices are a feature of many religious and spiritual practices. She also argues that psychotherapists, such as Freud and Bion, can be thought of as describing a mindful quality in the way they describe the therapist’s quality of attention within the session (Rapport, 2014).

Mindfulness in a therapeutic context can be defined as:

‘…a non-elaborative, non-judgemental, present-centred awareness in which each thought, feeling, or sensation that arises in the attentional field is acknowledged and accepted as it is. The present-centered awareness or way of paying attention is cultivated, sustained, and integrated into everything that one does…Within the client-therapist relationship, mindfulness is a way of paying attention with empathy, presence and deep listening that can be cultivated, sustained, and integrated into our work as therapists through the ongoing discipline of meditation practice. (Hick, 2008: 3)

There is a distinction between mindfulness-based therapy and mindfulness informed therapy that many therapists have found helpful in understanding different ways of incorporating mindfulness into therapy. In ‘mindfulness-based therapy’ mindfulness is taught to the client, by the therapist guiding mindfulness practices and through psycho-education. In ‘mindfulness-informed’ therapy, the therapist embodies mindfulness through their presence, communication and through relational mindfulness without specifically presenting instructional elements to the client. For Siegal, who has written extensively in this field, he differentiates the effect of the therapist’s ‘mindful presence’ and the effect of the teaching of mindfulness (Siegal, 2010: 32). Whether the therapist does or does not choose to guide the client in mindfulness practices, there will be ways to incorporate mindful qualities into the therapeutic relationship. This can include the ways in which the therapist uses her personal experience of mindfulness to inform her process, in the relationship, the content of the dialogue between client and therapist, and directing a client to notice a felt sense in his/her body during the session. Relational mindfulness is described as the flow of mindfulness between the therapist/client, and emphasises authentic speaking and deep listening (Beardall and Surrey, 2014).

In mindful art therapy, art-making can be either directive or non-directive. Peterson (2014) adopts a directed approach in her work with cancer patients. Her eight-week MBAT programme (mindfulness based art therapy), is closely linked to the MBSR curriculum and incorporates mindful exploration in using the art materials and directed image-making based on body sensing and feelings (Peterson, 2014). In a non-directed approach, the client is invited to use the art materials however they wish. In each approach there can be an emphasis on mindful experiences in art making, such as how the materials feel, and what is known, sensed and experienced in the body-mind during the making process.

When a person makes art they can experience a state of immersion, flow, focus and calm, accessing an inner witness, and being absorbed in present-moment experience (Rappaport and Kalmanowitx, 2014). Some mindfulness practices emphasise focus, such as awareness of the breath. This can enhance the capacity of the body’s parasympathetic nervous system, associated with calm, rest and repair, to bring the body back to a homeostatic state (Smalley, 2010). In making art in art therapy, clients may enter this state of focus. In art therapy, clients report that they find the process relaxational and calming. In both mindfulness and art making there is an orientation away from the habitual thinking mind, towards heightened feeling and sensing. It may be hypothesised that both processes promote the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

The mindfulness of art, the art of mindfulness

What is this art making process? Any attempt to dissect it falls through my fingers. I am here and I decide to make something with art materials. I either visualise an image or allow something to spontaneously emerge. My hands make contact with materials. My body moves. There is an activation of my imagination and my senses. An external form, outside me, manifests. There is constant change as the image evolves. The object, as it is created, shifts, transforms, is added to; possibly erased, possibly torn up or destroyed. There is something in observing this motion and fluidity that can be likened to the state of impermanence that is also known through mindful practice:

‘Just being alive means being in a continual state of flux. We, too, evolve, we go through a series of changes and transformations to which it is difficult to affix an exact beginning or exact end’ (Jon Kabat Zinn, 1990: 242)

In image making we also are in touch with this state of flux and transformation. What starts off as one thing, may end up totally different. We engage our senses: visualizing, touching, feeling, moving, hearing. The sound a chalk makes as it is dragged across the page; the motion of the arm as a roller moves from side to side. As in mindfulness, the sensing and non-verbal communication may promote heightened attention. A common image in mindfulness teaching is to view the mind as the sky and thoughts as clouds that pass, thus conceiving of the mind’s inherent sky-like nature. Perhaps we may recall this as we start off with a blank sheet of paper, ready to hold our act of creation: in the mind, there is a relationship between thoughts and spaciousness; in art making we may also play with this relationship between form and spaciousness.

There are some mindful qualities that are particularly relevant to art-therapy, and indeed may reflect how art therapists already work. These include the attitude of non-judgement (Smalley and Winston, 2014) and the inter-relational awareness between client and therapist within the session. A non-judgemental attitude is cultivated in art therapy by informing the client that the art in art therapy will not be judged, and that the intention of the art making is not an aesthetic one. The art is a medium for the client to express their feelings and experiences. This models a non-judgemental attitude, which can help the client relate to other views they may have in this way. The image is valued, along with all parts of their experience, and together there is an acceptance of whatever is externalised through the art. Sometimes a client will be pleased or proud of what they have produced, it may feel affirming; at other times, what is made may feel messy, confused, uncertain or broken. Each is accepted as how things are at this present time, with an understanding that all things will change.

Another quality inherent to mindfulness is compassion: mindfulness as ‘infused with warmth, compassion and curiosity’ (Williams and Penman, 2011: 173). This warmth and compassion may be embodied by the attitude of the therapist and in the relationship of curiosity between client and therapist about what is made.

Art therapy promotes play, even for clients who are adults! Clients are encouraged to experiment with materials. This supports them in accessing something innate from childhood, an inclination to make marks. Art making can be seen as a reclamation of our ability to play. This can support the development of a playful attitude towards other areas of our being, including our attitude to our mindfulness practice, such as noticing when there is tension and judgement and inviting ease and compassion to this.

Another quality of mindfulness is non-identification with thoughts (Smalley, 2010). Mindfulness teachers describe how, in mindfulness practice, one can notice both the observed and the observer. This has something in common with an aspect of art therapy. The relationship between client, therapist and an art object is unique to art therapy, and has been referred to as the triangular relationship. Through this relationship there is the externalisation of an inner experience. Client and therapist observe what is made together. In the act of the client making an object, there is a distancing from their inner experience, which promotes insight. Art therapy facilitates exploration of the whole self and the externalisation of inner states, including feelings and emotions. Together client and therapist explore what has been made. This can take the form of inquiry and dialogue. The client is encouraged to speak about their responses to what they have made and the therapist mindfully observes the making process. McNiff explores this process in depth in his writing on ‘witness consciousness’ (McNiff, 2014).

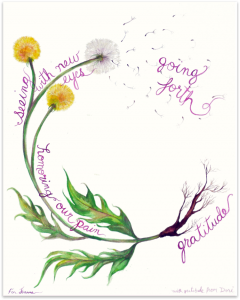

There is, perhaps, a commonality between a person who invests in practicing mindfulness and a person who invests in the process of art therapy. In practicing mindfulness there is an encouragement to be open to all aspects of the self: this complex, mysterious, body-mind; the unknown territory of what will emerge when we start investigating and knowing ones-self. We may feel like risk-takers in this process. In entering into art therapy there is also the willingness to explore our inner world, within the framework of the containing relationship. There is a potential to open our awareness to areas of oneself that are unknown; to be with the depths and range of experience, through verbal and non-verbal means, this can include states that may be subliminal, pre-verbal, dream-like, or illustrate dreams. In both the process of mindfulness and art-therapy there may be an experience of freshness as we bring insight into what this body-mind is. There may also be painful experiences and feelings that emerge, which in mindful art therapy are explored and supported, within the relationship. (Although mindfulness can be seen to emphasise present moment experience, this is not to reject an exploration of how past experiences can shape our present experiencing.) Likewise, the dynamic in the client/therapist relationship can be a mirror, and means of insight, into the impact of prior relationships on the client’s current experience.

Conclusion

Mindfulness approaches and art therapy, together, can offer a unique benefit apart from either offered in isolation. In mindful art therapy there is a complimentary meeting of work within a visual modality, the therapeutic relationship, and the practicing of mindfulness. The developing eight-week taught mindfulness courses described above have proven effective for treating a range of conditions, but may have some limitations, such as: what a person may require if they have material related to their past that needs further therapeutic work; if they have painful or sensitive experiences; or if traumatic memories have surfaced during their mindfulness practice. Mindful art therapy has the potential of providing a different type of framework and experience, including conditions for a safe, containing exploration of an individual’s experiences and feelings, within the therapist-client relationship, in which mindfulness is practiced. In art therapy, specifically, the individual’s visual expression is valued and mindful qualities are directly experienced through art making.

For a person to move towards increased health and wellbeing there may be a role to play for: psycho-education about mindfulness; experiential mindfulness practice; as well as, the personal growth that is possible through art therapy. Mindfulness can also be embedded in the practice of the art therapist. The mindfully-orientated art therapist can choose, based upon their client’s needs and the context in which they are working, whether or not to guide mindfulness and whether or not to include directed mindful art-making, with this decision based on the bedrock of the therapist’s own mindfulness-practice and knowledge of mindfulness approaches. The art therapist, through the lens of mindfulness, is enabled in the processing of their own feelings and bodily sensations during the session and the client is enabled to increase their capacity for curiosity, awareness and self-compassion.

Bibliography

-

- Beardall et al (2014) ‘Relational Mindfulness and Relational Movement in Training Dance/Movement Therapists. In: Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Fritsche, J. (2014) ‘Mind-Body Awareness in Art Therapy with Chronic Pain Syndrome’. In: Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Hick, S. and Bien, T. (2008) Mindfulness and the Therapuetic Relationship. Guilford Press, London.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990) Full Catastrophe Living. Piatkus, London.

- McNiff, S. (2014) ‘The Role of Witnessing and Immersion in the Moment of Arts Therapy Experience. In: Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Peterson (2014) ‘Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy: Applications for Heaaling with Cancer.’ In: Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Rappaport, L. and Kalmanowitz, D. (2014) ‘Mindfulness, Psychotherapy and the Arts Therapies’ In: Rappaport, L. (2014) Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. JKP, London.

- Segal, Z. Williams, M., Teasdale, J. (2002) Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. Guilford Press, New York.

- Siegal, D. (2010) The Mindful Therapist. Norton, London.

- Smalley, S. and Winston, D. (2010) Fully Present. Da Capo, Philadelphia.

- Williams, M. and Penman, D. (2011) Mindfulness Finding Peace in a Frantic World. Hatchette, London.

The following information is an introduction to The Work That Reconnects, based on the teachings of Joanna Macy, and the book Active Hope she co-authored with Chris Johnstone. The text below is also informed by recent workshops and presentations by other teachers, activists and thinkers who have been speaking in relation to climate crisis , racial justice, social justice and climate justice, including during a recent Awakened Action Conference, broadcast online by Upaya Zen Centre (Bibliography below)

The following information is an introduction to The Work That Reconnects, based on the teachings of Joanna Macy, and the book Active Hope she co-authored with Chris Johnstone. The text below is also informed by recent workshops and presentations by other teachers, activists and thinkers who have been speaking in relation to climate crisis , racial justice, social justice and climate justice, including during a recent Awakened Action Conference, broadcast online by Upaya Zen Centre (Bibliography below)